By Nicole Anderson and Brian Donovan, Oregon State University

Previous blog posts provided by Purdue University (Braun and Patton) and Oregon State University (Kowalewski et. al.) turf personnel have done an excellent job of describing fine fescue taxonomy and providing an overview of the characteristics associated with the five kinds of fine fescues, respectively. Discussions about fine fescues are often associated with their uses as low-input turfgrasses in homeowner lawns, public green spaces, and golf course fairways. As fine fescues draw more attention because of their low-input turf attributes, it is critical that a reliable and consistent supply of seed is available in the consumer marketplace. The science of seed production (Figure 1) is relatively understudied in crop research communities and turfgrass consumers are often equipped with very little information about the process of producing high quality seeds, which are needed to keep the market supplied. This blog post will briefly describe fine fescue seed production in Oregon and discuss the role of open-field burning to maintain a necessary seed supply.

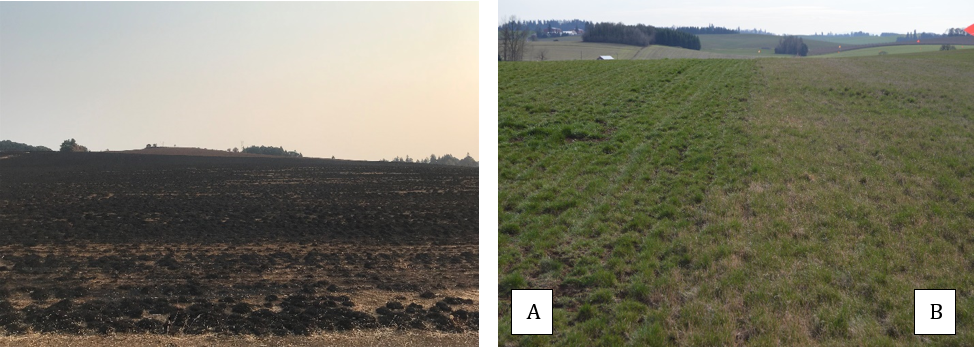

Oregon, often referred to as the “Grass Seed Capital of the World”, produces approximately 400,000 acres of grass seed crops, annually. Oregon is an ideal growing environment for grass seed crops because of the unique temperatures of its climate with warm-dry summers and cool-wet winters. In addition, many soil types can be found over relatively small distances, which support diversified crop rotations and the ability to adapt to changing seed market demands. While Oregon is the largest producer of grass seed globally, there are several other important fine fescue seed growing areas including regions of Canada, Denmark, and the United Kingdom, among others. Less than 10% of Oregon’s total grass seed production area is comprised of fine fescues that include strong creeping red fescue, slender creeping red fescue, Chewings fescue, sheep’s fescue and hard fescue. However, there are specific geographic areas, including the Silverton Hills, Columbia Basin, and Grande Ronde Valley where fine fescues are especially well suited to the specific soils and cooler climate. Currently, about 60% of Oregon’s fine fescue seed production occurs on the moderately sloped silty clay loam soils of the Silverton Hills, located in the foothills of the Cascade Mountain range. Rainfall amounts of 45 inches or more between October and June are common, making dryland production quite successful. Fine fescue crops are generally harvested for 3-5 years and are commonly rotated with other field crops such as perennial ryegrass, meadowfoam, clovers, and cereals. Historically, grass seed farmers have been able to produce highly dependable fine fescue seed yields in part due to the ability to practice thermal residue management practices (open-field burning) after harvest (Figure 2). While growers have faced restrictions in recent years, open-field burning is still an important practice for reducing post-harvest residue, recycling nutrients, and managing unwanted pests in fine fescue crops.

Grass seed production is a highly specialized enterprise (Figure 3), which includes planting, managing pests and nutrients, and harvesting at appropriate seed moisture levels with equipment designed especially for capturing and cleaning small seeds. Once seeds are mechanically removed from the field, they must go through the seed conditioning process to remove unwanted contaminants such as soil, straw, and weed seeds. Samples from cleaned seed lots then undergo numerous seed certification and seed quality testing requirements to ensure required field isolation and optimum seed quality, purity, germination, and vigor. While the seed conditioning, certification, and testing processes can be lengthy and expensive, this is a critical step in ensuring that high quality Oregon grown seed is made available for consumer use.

As part of the Low Input Turf grant, we are evaluating combinations of agronomic management practices and their effects on seed yield in a non-thermal environment (no open-field burning). Specifically, field trials are focused on determining interactions between spring nitrogen, mowing, and plant growth regulators in both creeping red fescue and Chewings fescue, across different stand ages. The objective of the project is to equip seed growers with research-driven information that can be used to make informed decisions if/when they are producing fine fescue seed crops in the absence of open-field burning. This is an important step towards ensuring an adequate fine fescue seed supply into the future.